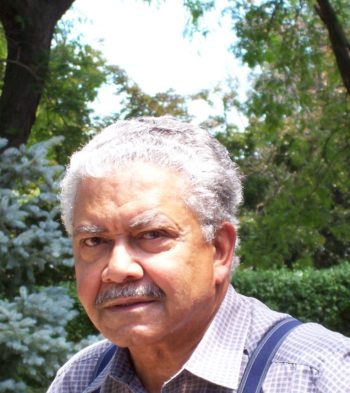

A porter’s pride

by Gerry Archambeau

There is no perfect job that I know of, but for a black person in the 1940s and ’50s, it was as good as it got. This was one of the few jobs that openly welcomed black men of those days.

Working for the railways in Canada was a positive experience for me. Too many people have a tendency to bite the hand that feeds them. There has been much attention given to the negative experiences of the black men working the Canadian railways, stories about workers suffering under oppressive bosses and passengers, while in some sort of bondage to the railroad companies. Porters were portrayed as if we were the lowest form of human life. This is the sort of portrayal that gives the wrong perception to young Canadians.

The truth must be told by those like myself who were there.

Who were these men who stood so elegantly at the doors of these beautiful trains, in their clean white linen coats and shiny shoes, with a welcoming smile that beamed fram their dark faces?

These men were mostly from the Caribbean and the United States, along with born African-Canadians. No other institutions that I can recall gave black men an opportunity like the railways did, to rear their families with dignity and enable them to educate their children. These gentlemen, who served the travelling Canadian public of the 1900s to the 1960s, were a credit to Canada’s development. Some, like me, came from the Caribbean islands. Many came from the United States trying to escape the tyranny of rampant racism.

Many were well-educated men without any other prospects for a decent job. The railway offered clean and spotless surroundings, cool in summer, warm in winter. To be well fed while on the job was quite a change for me. I thought of it as a stepping-stone to move forward in a country that was trying to settle immigrants fmm all over the world. The railway companies made it possible, like it or not.

Black Canadians should be proud of their relatives who worked the railways, who made a living so their children could be educated today, rather than have a negative attitude regarding what their fathers did as some sort of low, menial work.

My own history begins in Jamaica in 1933, growing up with an aunt and extended family. I was sent to Montreal in 1947 to join my mother and new stepfather in Canada. I was 13 years old, and, instead of being sent to school, was told to find a job. The next two years I bounced around among a number of low-paying jobs until age 15. ‘Ihen I was thrown out of the house by my stepfather. Friends of my family took me in and new friends within Montreal’s black community suggested I try my luck with the railways as it was the best-paying job a black man could get at the time.

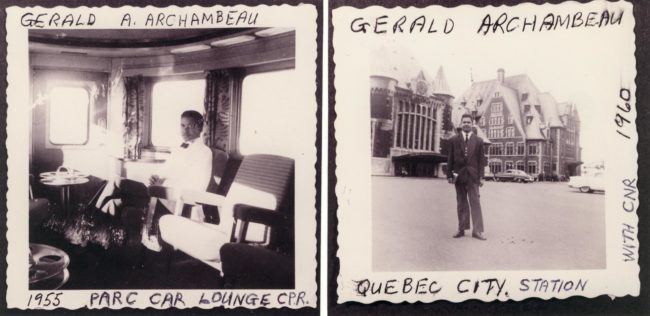

In 1951, at age 19, I made my first working trip out of Montreal’s famous Windsor Station on the Canadian Pacific Railway.

A porter’s job consisted of making up beds in his car, seeing to his passengers’ needs and cleaning shoes that were left in a box at night. Men’s pants could be pressed if needed in the club car, and that is where the good tips were usually given. The porter’s uniform had to be clean and spotless at all times, and I remember bringing as many as six white shirts per trip, depending on the distance to be travelled. Our appearance was constantly monitored and checked by the porter instructors.

Porters had to be very trustworthy, so passengers could leave their valuables behind while they dined or sat in the club car. Some people would drop off their sons and daughters to be looked after by a porter as they travelled, to arrive safely at the other end and be picked up by relatives. That’s trust, I think.

The job paid a good salary, gave job security if you obeyed the rules and it had a pension plan. But the thing that most former porters will not tell you is how very well a porter could do by giving good service to his passengers who usually tipped quite well, and it was tax free.

I remember being asked, “How can you guys dress so well all the time?” Some tailors in Montreal, such as Golds & Sons on St. Catharines Street, made a bundle from the average railway porter.

That is why most black men stayed on the railway until the end, even when other jobs became available to them in the

1970s.

It was a time when riding the railways was often viewed as a luxury. I met a large cross-section of Canada’s people, including businessmen, families and many of the wealthy people of our society. Most of these people could afford the luxury of sleeping- and dining-car service, with porters and waiters looking after them all the way to their destinations.

I became quite good at my job as time went on, which gave me the opportunity to serve many of our provincial premiers, and some prime ministers of Canada. This privilege included a special trip with John Diefenbaker in 1957, when I was assigned to a sleeper-lounge car for the reporters. It was next to Diefenbaker’s private car at the back of this special Canadian National Railway train. During a two-week campaign trek across Canada, Mr. Diefenbaker and his wife would come for afternoon tea in my car, and speak with the reporters.

Special trips also included most of our great hockey teams in the NHL of the 1950s and ’60s, with their star players such as Maurice (Rocket) Richard and many other fine players of that time. My contact with the players was limited because they were usually dead tired after a game, but I could always get an autograph from any of them in the morning, plus a generous tip from the head coach for my good service.

Vexy few bad or racist encounters ever occurred on my many trips. However, a porter was sometimes called “Boy” or “George” in reference to George Pullman, who invented the sleeping car. This would occur more often after heavy drinking. Drunks could cause problems on any part of a large passenger train, and if there were an incident, the white train conductors would intervene immediately, once it was brought to their attention.

The Canadian railways had very strict rules on crew and passenger behaviour. The majority of my trips were very pleasant ones, and most of the travelling public that I served was quite respectful to me. Canadian travellers in those days were good, decent people who just wanted to enjoy the trip.

Not everyone’s experience was similar. Many have told stories of poor treatment and racism. The history of railway work is filled with these.

American industrialist George Pullman was known to take advantage of the available African-American workers to operate his sleeper cars, paying much lower wages than to his white workers. Some were required to work hundreds of hours per month or thousands of miles in the railroad before getting any pay. They depended on getting those good tips to make a decent wage, as those tips could often amount to more than the actual salary.

A porter would be asked to take the train from Montreal and travel with his sleeping car across the country to Vancouver for five nights and days, and only be allowed three hours of sleep each night. After arriving, he would have a layover in Vancouver for two nights before returning to Montreal.

This practice was stopped by the work of men who stood strong within the union ranks. Thank goodness this practice by the railways was over when I started, so we only went as far as Winnipeg where a fresh crew took over, then we had a day to rest before returning.

These great passenger trains went to all the major cities and towns in Canada, and crossed border into the U.S. The number of black men needed to operate these trains kept growing, and in Canada that resource was limited. So unlike the U.S. railroads, the Canadian railways had to hire white waiters and cooks for their dining cars. The black unions were able to get better conditions as time moved on, such as fewer hours of work.

Many passengers were shocked to see white porters coming on at Winnipeg to take the transcontinental trains through to Vancouver. Things began to change for the better as Canada did not have enough black men to pigeonhole anymore.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, headed by A. Philip Randolph in the United States and Arthur Blanchette in Canada, was the greatest break for black workers in those days. The union organized in 1925, during the peak decade when thousands of African-Americans and African-Canadians worked the rails, creating the largest category of black labour in Canada and the United States.

The first contract came in 1937, years before I worked on the railroad, but the lingering effect of the union was better working conditions for black porters across Canada and the United States.

On April 24, 1955, I was assigned to the Canadian Pacific Railway’s brand new “Canadian” on its first run across Canada. This new train was the CPR’s last passenger-train purchase to compete with the Canadian National Railway’s Super Continental.

The Canadian had all stainless-steel cars, and was the first train to operate dome cars in Canada. It was filled with modern luxuries, along with beautiful painted Canadian scenes in the eating and lounge areas. This was railway history at its best and was proud to be a part of it.

Canada now had four transcontinental trains crossing this great country seven days a week, year-round. How wonderful it was to ride on them while seeing the vast countryside close-up.

New diesel engines were now pulling an average of 15 cars, carrying most of the travelling Canadian population in safety and comfort from town to city, and through the images of this land. From the East Coast to the West Coast, these prestigious trains ran like the wind, over all terrain and in all kinds of weather. Trains such as The Gun, The Maple Leaf, The Maritime Express, The Dominion, The Northland, The Alouette, just to name a few.

It would all come to an end by the late 1960s, when the travelling habits of Canadians changed. Passenger rail travel eventually gave way to the airlines for speed or auto transportation for individual convenience.

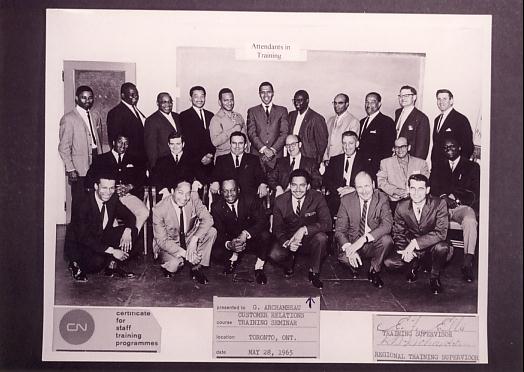

I moved on to air, joining Air Canada in 1967, transferring my CNR pension to the airline and working until early retirement in 1993.

Canada as a country was changing fast too, and for the better. Basic human rights and fair employment pracüces for all men and women was eventually legislated throughout the provinces of Canada.

Surprisingly, I found a lot more racial intolerance in the airline industry than I had experienced as a porter on the

Many of the men I worked with on the trains over the years went on to get very good jobs and professions after the drop in popularity of railway passenger service. So what is there to be ashamed of? The children of these black men and women have thrived all across this wonderful county.

These railway men gave their service to the public, and faded into a more just Canadian society, like the great trains they rode. They served as sleeping-car porters, parlour-car attendants, club-car stewards and porter instructors. They served with dignity.

It is important for a new generation of young Canadians to know the truth about these fine black men who gave much to Canada.

About the writer

Gerald A Archambeau lives in St. Catherine’s. His autobiography: “A Struggle to Walk with Dignity: The -Story of a Jamaican-born Canadian”, was published by Dundurn Press in 2008 .