Saint John native Abraham Beverley Walker was a ‘fascinating’ man, says local amateur historian

Bobbi-Jean MacKinnon · CBC News · Aug 11, 2019

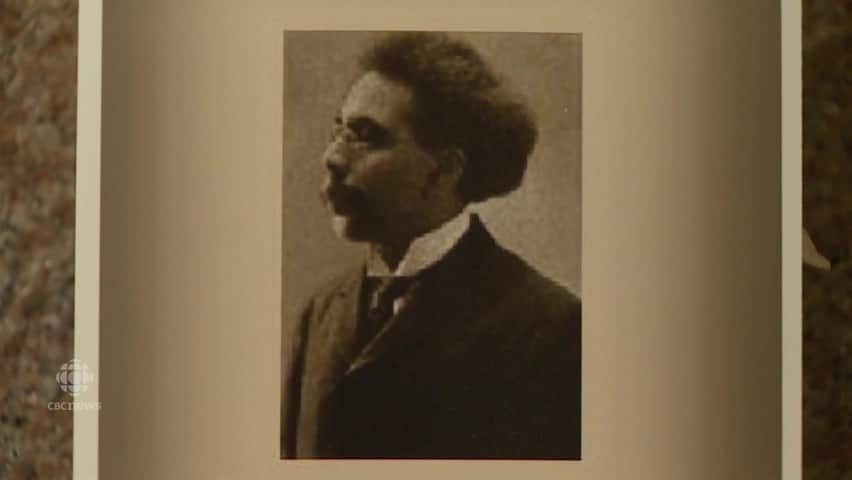

Abraham Beverley Walker was the first Canadian-born black lawyer, but the Saint John area native has been all but forgotten by history, says a local amateur historian.

Peter Little hopes to change that.

“The way I look at it is, this is righting a wrong,” said Little, who successfully applied to have Walker honoured posthumously with the Order of New Brunswick this fall.

“He’s been dead 110 years and forgotten about completely. Probably the most intelligent man of his day, snubbed and even ridiculed in open court by other lawyers. So it’s high time he got some recognition.”

Little has been hooked on history since he was a boy, when his parents gave him the book, An Intimate History of New Brunswick.

He has added more than 100 local history books to his collection over the years and read many more, but says he had never come across any mention of Walker.

He started researching him at the request of Ralph Thomas, a founding member of the New Brunswick Black History Society, and was quickly struck by the “fascinating” man.

“It took a lot of digging,” but he discovered Walker was a highly educated and well-travelled lawyer, journalist and civil rights activist whose articles and speeches reminded him of the late Dr. Martin Luther King.

Walker even has his own “I have a dream” speech, said Little. He used the metaphor of an actual dream, where he saw the five major races — white, black, Indian, Malay and Asian — fighting, committing crimes and sins.

“And at the end, he talks about how they walk out into the sun and a new day when hatred … and all these other things … are no more. And they laugh at the foolishness of their past times.”

Born in 1851, Walker came from humble beginnings, growing up in a large family in the rural community of Kars. He was educated in a one-room schoolhouse, studied shorthand under an Anglican preacher in Kingston, N.B., and went on to study law at National University in Washington, D.C.

CBC News New BrunswickPeter Little successfully applied to have Abraham Beverley Walker recognized with a posthumous Order of New Brunswick00:00 01:29Abraham Beverley Walker (posthumous), from Saint John was recognized “for his inspiring achievements as Canada’s first black lawyer admitted to the bar and for his commitment to civil rights in New Brunswick and across North America.” 1:29

In 1881, Walker was admitted as a solicitor to the Supreme Court of New Brunswick.

He was called to the bar the following year. A decade later, he was the first student of any colour to enrol in the Saint John Law School, which had just opened.

Walker practised law for a few years, with an office on Princess Street, but “racism was systemic and institutional,” said Little.

In 1885, for example, a local barrister organized a celebration for the Law Society and invited every lawyer — except Walker, he said.

Walker was promised a Queen’s Counsel appointment, but when the local white lawyers found out about it, they went to the attorney general “and said, ‘If you give this man the Q.C. we’re going to renounce ours.’ So they took his name off the list.”

Saint John native Abraham Beverley Walker was a ‘fascinating’ man, says local amateur historian

A few years later, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier promised Walker a King’s Counsel appointment, but was talked out of it by a racist, according to Little.

Walker, who had a wife and five children to support, decided to work as the librarian of the local law society, but became heavily involved in the “promotion of what he called ‘fair play and justice;’ what we call civil rights today,” said Little.

He “went on the lecture circuit,” travelling the continent and later moved to … Georgia because of its growing black middle class, with black schools and universities and some professionals, such as doctors and clergymen. He thought it would offer more opportunities for his family, said Little, but he soon returned to Saint John “completely disillusioned and bitter” about the segregation laws and commonplace lynchings.

In 1903, Walker became the first black New Brunswicker to publish a magazine. Neith. It focused largely on race issues, but also dealt with history and philosophy, literature and art.

Walker wrote about a lynching in one of his articles and faced sharp criticism for it by the whites, said Little. “They didn’t want to hear that kind of stuff. They thought they were doing just fine,” he said.

Walker later founded and promoted the African Civilization Movement. His vision was to recruit educated and industrious blacks from across Canada and other developed nations to build a model colony for blacks in Africa.

Search for descendants

On Oct. 30, Walker will be invested posthumously into the Order of New Brunswick “for his inspiring achievements as Canada’s first black lawyer admitted to the bar and for his commitment to civil rights in New Brunswick and across North America,” according to a government news release.

Little will accept the award on Walker’s behalf during the ceremony at Government House, when nine other recipients will also be honoured.

He said the award — the province’s highest civilian honour — rightly belongs to Walker’s descendants, but he hasn’t been able to connect with any of them yet.

Two of Walker’s children died in their early teens, a son died when he was 20, before he had any children, and a daughter married, but contracted tuberculosis and died a year later.

His son, George, was the only one who lived and raised a family. Little believes he has traced his descendants to Wisconsin and is trying to reach them.

For now, the award will be held in trust by the New Brunswick Black History Society, he said.

Little also hopes to secure a marker for Walker’s grave and is looking into getting a street or school named after him.

With files from Rachel Cave