Image copyrightSMART FACTORY

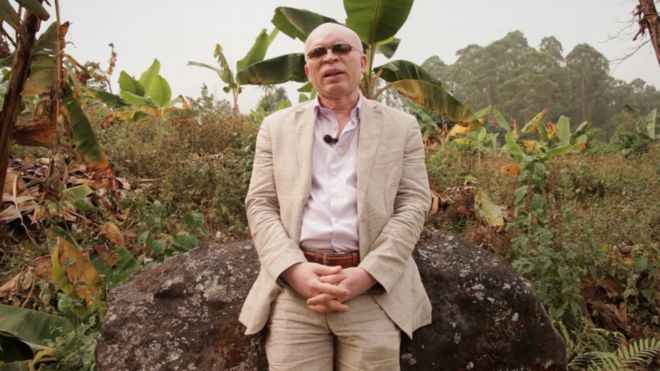

Image copyrightSMART FACTORYStephane Ebongue stands nervously at the edge of a forest trail, dressed in a suit and carrying a briefcase. His dark sunglasses are a necessity because he has albinism, but they also hide his nervousness. “My heart is beating fast. I have never come to a place like this before,” he says.

This is the day he hopes to find answers he has spent years searching for. The trail leads to a witchdoctor who trades in albino potions.

“I would like to find out why albinos keep getting killed. Maybe the secret lies at the end of this path,” he says.

Ebongue is a journalist, a rational man who deals in facts. He does not believe in magic, yet he is deeply unsettled about this meeting.

Across Africa, in countries such as Tanzania, Malawi and Ebongue’s own country, Cameroon, there is a belief that people with albinism bring luck or have magical powers. This has devastating consequences for those with the condition.

“It is believed that parts of an albino, such as their heart, hair or fingernails, are important to make magical potions – for instance to fertilise the soil, to become invincible, to win political elections or a football match,” says Ebongue.

“This is why albinos are killed and mutilated for the parts of their body.”

According to a recent UN report, such body parts can fetch prices from $2,000 for a limb to $75,000 for a “complete set” – a whole body.

Ebongue was 15 when his older brother, Maurice, who also had albinism, went missing 30 years ago.

“He went out one morning and did not come back,” says Ebongue.

Days later the family found the 18-year-old’s body in some bushes. He had been mutilated. “His stomach was opened – I don’t know what was missing inside,” says Ebongue.

Ebongue’s parents tried to give their two sons with albinism a normal childhood – they treated them the same way as their other children – so it wasn’t until he first went to school that he realised he was different. His classmates would ask him, “Why is it that you are white and we are black?”

“They were coming to touch my skin thinking that I had put talcum powder on there,” he says.

At first he got into fights at school but his parents, both teachers, knew what to do.

“They understood the problem and pushed me to study harder.

“My revenge was that I was always the first in my class.”

The trouble was that like most people with albinism, Ebongue had very poor sight, which made it difficult for him to read small print or see the blackboard, even when he sat at the front of the class.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES“During official exams there were many times where I had to hand in a blank sheet of paper,” he says. “Not because I wasn’t up to the task, but because the script was written so small that I could not read it. I had to give back a blank sheet of paper and go out crying.”

He swore to himself that he would one day create a library where visually impaired people like himself would be able to read with ease.

Ebongue went to study journalism and English literature at university, where he was the only student with albinism out of 10,000. His uniqueness made him a point of reference in the local community. “People would say, ‘Where the house of the albino is, meet me there,'” he says.

By 2007, at the age of 37, he was married and working as a journalist in Buea, in the shadow of Mount Cameroon, one of Africa’s most active volcanoes.

It was the volcano that caused a huge crisis in Ebongue’s life.

“It is believed that when there is an eruption it means Epasamoto, the god of the mountain, is angry,” says Ebongue. “To calm him down they need the blood of an albino.”

When the volcano had erupted in 1999, lava flowed down the side of the mountain, stopping just short of Buea. There were no casualties, but the traditional doctors claimed that the town had been spared only because albinos had been sacrificed.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESIn 2007 there were fears of a new eruption and people were doing “everything possible” to stop it. At times like this, when what Ebongue calls a “general psychosis” takes hold, people with albinism go into hiding.

Fearing for his life, Ebongue decided to go abroad. His wife and three children, none of whom had the condition, were safe – they could follow at a later date, he thought.

He found a captain willing to smuggle him on board a ship carrying timber to Italy, and spent 33 days hidden in the dark hold.

“I was asking myself many questions without answers, so it was mentally and psychologically very difficult,” he says.

“I was suffering. I had left my wife and my children, I had left my job, I had left my country, I had left my friends.”

Soon after arriving in Genoa, Ebongue was granted refugee status on humanitarian grounds.

Living in Italy was liberating. For once, his colour was an advantage – other Cameroonians would regularly be stopped by the police, whereas he was not.

“When I lived in Africa I had three enemies: the sun, the people’s disgust and the fear,” he says.

“Here, I don’t have such problems. I feel freer here, I feel free to move, I’m not ashamed.”

In his new home, Ebongue found he was provided with specialist sun cream as well as a magnifier, to help him read. He had never seen anything like it before – and when he saw what it could do, he burst into tears. Before it would take him two months to read a novel. With the magnifier he read 10 in a month. “I was trying to make up for lost time,” he says.

The experience made him even more determined to build a specialist library in Cameroon.

Image copyrightLE PAVILLON BLANC

Image copyrightLE PAVILLON BLANCEbongue soon learned Italian and settled in Turin, where he taught the language to new arrivals, and made a new friend in local journalist Fabio Lepore.

The two men bonded because Lepore, too, has a visual impairment. His is caused by macular degeneration – Stargardt disease – which means he has 2/20 vision in both eyes. “I was lucky because I started to lose my sight at the age of 16, so I could learn how to do without,” says Lepore. “I can’t drive a car – but I can paraglide.”

They began working on a documentary about Ebongue, called Jolibeau’s Travels – Jolibeau is the nickname he is known by at home in Cameroon.

And this is why, five years later, Ebongue was standing by the side of a road in Cameroon, about to meet a witchdoctor, and struggling to keep control of his emotions.

“I was there as a journalist,” he says. “I wanted to meet somebody who could explain to me the deep roots of those beliefs, and I thought a native doctor could do that.”

At the same time, he knew that many people with albinism – among them his own brother – had died at the hands of people like the man he was about to meet.

After a 20-minute walk through the forest, the documentary footage shows Ebongue and Lepore arriving at a clearing in the forest, where some washing hangs on a line next to a rudimentary wooden hut.

The witchdoctor comes out to meet them, wearing an orange tie-dye shirt and shorts. He shakes hands with them all, giving Ebongue a strange look.

Image copyrightSMART FACTORY

Image copyrightSMART FACTORY“You can see how the sorcerer looked at him, like a treasure in front of him,” says Lepore.

“He looked at him like a lion looks at a gazelle.”

The men follow the witchdoctor into the wooden hut where he receives clients. They walk past the remains of a ritual he’s performed the night before – some sort of animal sacrifice.

Ebongue begins by handing over a present of some whisky, and the agreed fee of 5,005 francs ($8.70, or £6). In return, the witchdoctor gives him some twigs to hold – he does not explain why.

Image copyrightSMART FACTORY

Image copyrightSMART FACTORYFormalities over, Ebongue asks his first question. “How are albinos considered within the traditions of this country?”

But the witchdoctor isn’t really listening. He’s staring at the treasure sitting in front of him.

“You do not even know your value. How much you’re worth,” he says to Ebongue.

“Albinos are in great demand – albinos just like you. From your hair to your bones, you are so sought-after.

“So much so that if we hear that an albino has been buried somewhere we go and find them in order to recover some parts which are really important and help us.”

Holding his emotions in check, Ebongue continues asking questions. The witchdoctor says he receives up to four clients a week in busy periods, and that all kinds of people ask for “albino potions” – from farmers hoping for a good harvest to women trying to seduce a white man.

“Are you aware of the fact that the number of albinos is diminishing and that it’s not good to kill human beings to make sacrifices?” asks Ebongue.

“People go in search of money. They kill albinos not for the pleasure of killing them but to make money. That is why they get killed,” says the witchdoctor.

“Are you not scared that one day the police will come and find you because you work with the bones of human beings?” Ebongue asks.

“What do the police want? Money. If they come we will agree.”

After an hour or so of questioning and after sharing some palm wine, the visitors take their leave.

Image copyrightSMART FACTORY

Image copyrightSMART FACTORY“The only thing I wanted to do was to get out of there,” says Ebongue, whose survival instinct had eventually kicked in.

But when he looks back at the footage now, he is angry.

“Each time I watch the interview I’m shocked and I ask myself why I didn’t react,” he says.

If he could go back, he would do things differently. “I’d ask him whether he’s cheating people. I’d be more offensive, more aggressive.”

Instead of getting an real answer to the question why people like him are persecuted in Cameroon, all he found was a man out to make money.

Ebongue now wants to stop talking about superstitions and start talking about the real problems of albinism: health and education.

Image copyrightHANNAH MCNEISH

Image copyrightHANNAH MCNEISHDeadly sun

Without the protective pigment melanin in their skin, people with albinism are highly vulnerable to skin cancer. Just 2% of the 17,000 people with albinism in Tanzania (which has the highest rate of albinism in the world) live beyond the age of 40. Now a dermatology centre in the country has developed a sunscreen specifically designed for people with albinism, which could save many lives across the continent.

Listen to the report on Health Check on the BBC World Service

The biggest killer is the sun – the UN reports that in Africa most people with albinism die from skin cancer between the ages of 30 and 40. The problem is compounded by the fact that so many work outdoors in menial jobs, having dropped out of school because they can’t see.

Thanks to one Italian donor’s generous donation of 11,000 euros (£8,650), Ebongue was finally able to set up the library he dreamed of as a child.

At Le Pavillon Blanc Library in Cameroon’s largest city, Douala, visually impaired people can read freely thanks to magnifiers and other vision aids. About 70 people have joined the library, most of whom have albinism. Users currently have to pay a small fee – but Ebongue hopes to get government support for his project soon.

Image copyrightLE PAVILLON BLANC

Image copyrightLE PAVILLON BLANCHis aim is to help people with albinism make a success of their lives, to show that they are human beings like everyone else.

He still teaches Italian and presents podcasts for a web-radio station called Cameroon Voice, but the majority of his time and energy is invested in the library.

He travels back to Cameroon regularly to oversee the project and to visit his family, who were never allowed to join him in Italy. After six years of waiting, his marriage broke up. But Ebongue does not feel sorry for himself.

“At the end of the day, my story is a happy story. I went to school, I have a job, I got married, I have children,” he says. “There are people who cannot say the same.”