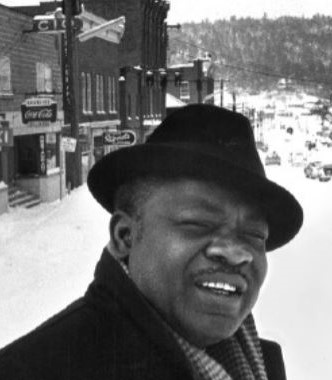

How Saint-Firmin Monestime made history as Canada’s first Black mayor

He was a political trailblazer with a storied and eventful life — but few outside northern Ontario have heard of Saint-Firmin Monestime, who, in 1964, became Canada’s first Black mayor.

Political turmoil and unforeseen circumstances combined to bring him from his native Haiti to the town that he later called home: Mattawa, 70 kilometres east of North Bay.

Born in Cap-Haïtien in December 1909, Monestime grew up during the United States occupation. One of seven children, he was able to pursue his education thanks to support from his father, a successful tanner, and he graduated from the University of Haiti with a medical degree.

In his 2009 biography of the politician, Where Rivers Meet, author Doug Mackey notes that Monestime was on duty in October 1937 when Dominican Republic president Rafael Trujillo ordered the killing of Haitians who were living in the border region. It’s still unclear how many died in the so-called Parsley Massacre —estimates range from 1,000 to 30,000 lives lost. “I saw all kinds of broken bodies,” he told Ebony magazine in 1965. “I helped bury the dead.” Soon after, Monestime received Haiti’s highest honour, the Chevalier de l’Ordre National d’Honneur et de Mérite (National Order of Honour and Merit).

But he grew frustrated with the political strife in his homeland, and, in 1945, he departed for Canada. Before he left, he separated from his then-wife, and she and their two children stayed behind, although Monestime continued to support them.

He settled in Quebec in 1945, but his medical qualifications were not recognized by the province. So he went back to med school at the University of Ottawa, graduating as a doctor in 1951. He met Zena Petschersky, a Russian refugee, at a Christmas party. The two later married and had four children — one girl and three boys.

Monestime eventually decided to set up a practice in Timmins. But his plans changed on the drive north to scout out the city. During lunch with a colleague at Chez Francois, in Mattawa, the owner of the restaurant told him that one of the town’s doctors had just died and that he’d be willing to provide Monestime with an apartment and office space if he were willing to stay. The doctor agreed.

According to his children, the people of Mattawa welcomed the doctor and his family, then the only Black residents in the town of roughly 3,000 people. His practice grew — he was known to make house calls at all hours of the day and night.

He also became increasingly interested in politics: a proud Progressive Conservative, he was drawn to the party in part because of the John Diefenbaker government’s introduction of the Canadian Bill of Rights, in 1960.

The interest then turned to action: In 1962, Monestime was elected to council. In 1964, he made history when he became the first Black mayor in the country.

“He received congratulatory telegrams and letters from all over, including the government of Mauritius, which stated that such an event gave everyone hope,” says his daughter Vala Monestime Belter.

Monestime later became a national director of the PC party and remained active in local politics until 1977, serving as mayor and councillor.

His later life was marked by tragedy. In 1976, one year before Monestime’s death from pancreatic cancer at the age of 67, his son Fedia — an innocent bystander — was shot in the stomach during an altercation at a motel in Mattawa. According to the North Bay Nugget, Monestime was on medical standby that night and treated three people wounded in the same incident — Fedia died on the way to the hospital.

“He had saved all these people, and he couldn’t save my brother’s life,” says Vala. “It was devastating.”

Before Monestime died, he accomplished one of his biggest goals: establishing and opening the Algonquin Nursing Home, a 60-bed long-term-care facility, in 1976.

“To this day, the people of Mattawa still see it as what he gave to them,” says Vala. “He would be pleased, satisfied, and comforted with how much it has grown. This is what dad wanted.”

His children continue to remember the accomplishments that didn’t make the news: he was a talented dancer; he made bamboo kites at the family cottage; he gambled away his Cadillac in a card game. They just wish that more Canadians were familiar with his legacy.

“I think more people should know about him,” says his son Yura Monestime, an associate dean at Canadore College in North Bay. “I don’t know if outside of northern Ontario, Parry Sound, if people know about my dad.”

Source: TVO