Desmond Tutu – South Africa’s rebellious priest

Saturday, 25 December 2021

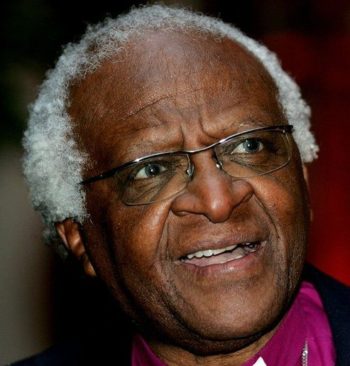

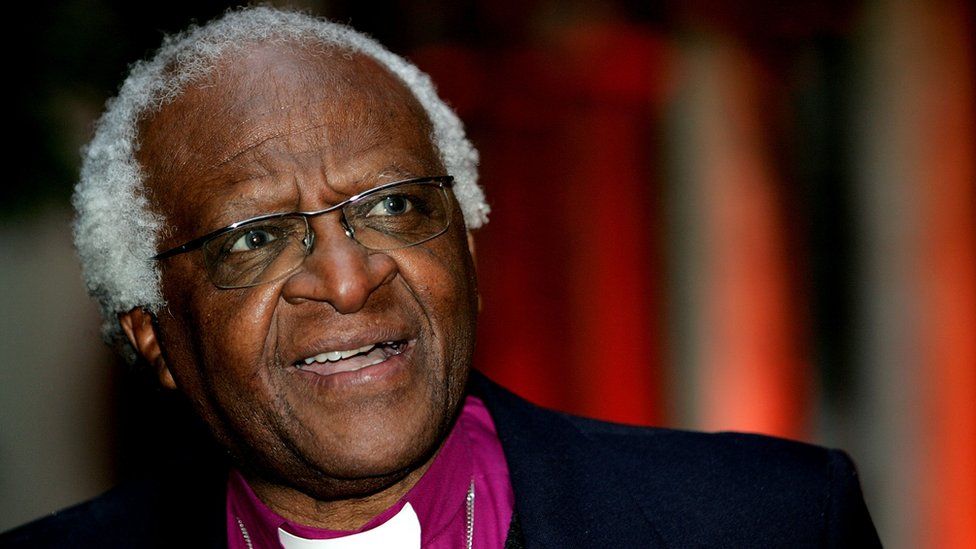

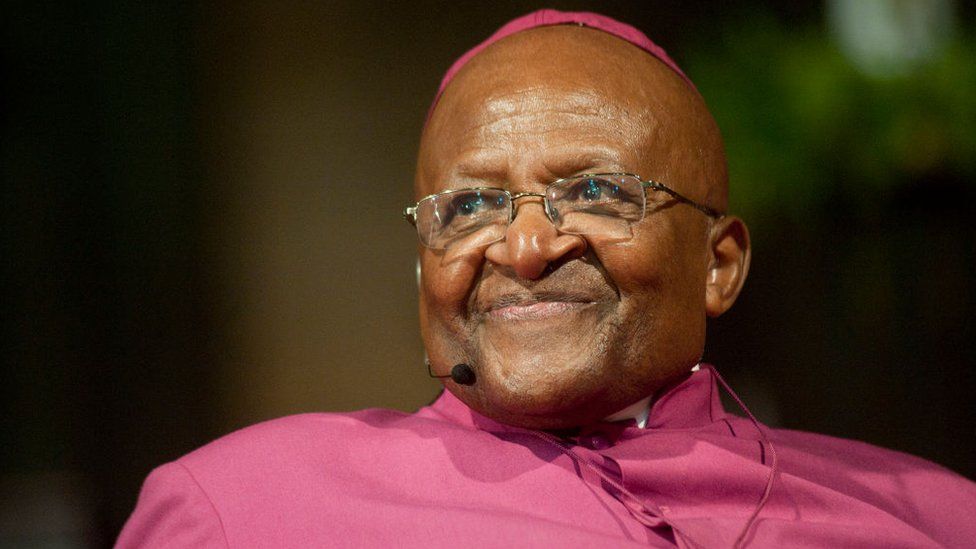

Desmond Tutu was the smiling South African archbishop whose irrepressible personality won him, friends and admirers, around the world.

As a high-profile black churchman he was inevitably drawn into the struggle against white-minority rule but always insisted his motives were religious, not political.

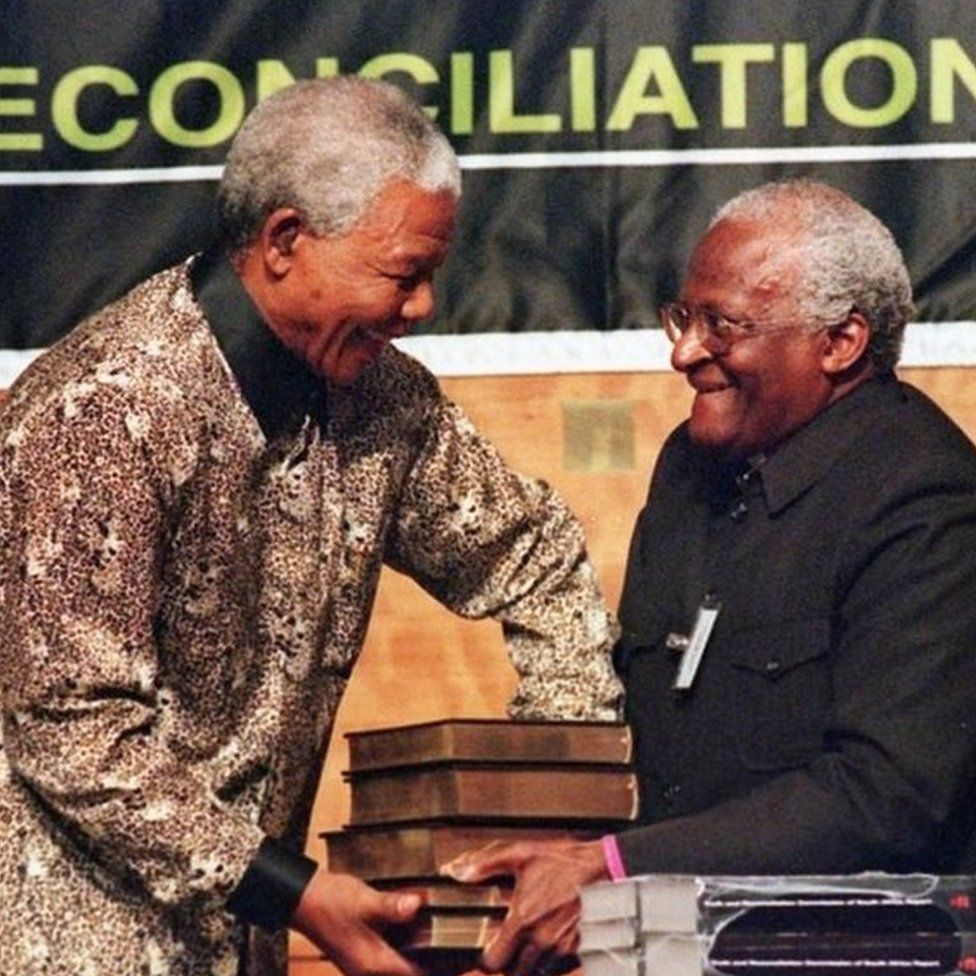

He was appointed by Nelson Mandela to head South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up to investigate crimes committed by both sides during the apartheid era.

He was also credited with coining the term Rainbow Nation to describe the ethnic mix of post-apartheid South Africa.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born in 1931 in a small gold-mining town in what was then the Transvaal.

He first followed in his father’s footsteps as a teacher, but abandoned that career after the passage of the Bantu Education Act in 1953 which introduced racial segregation in schools.

He joined the church and was strongly influenced by many white clergymen in the country, especially another strong opponent of apartheid, Bishop Trevor Huddleston.

He served as bishop of Lesotho from 1976-78, assistant bishop of Johannesburg and rector of a parish in Soweto, before his appointment as bishop of Johannesburg.

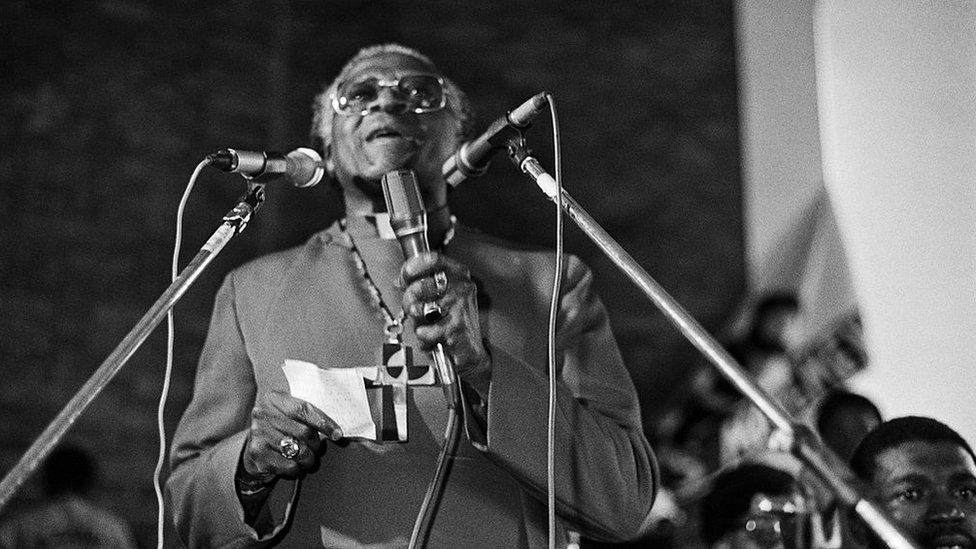

It was as a dean that he first began to raise his voice against injustice in South Africa and again from 1977 onwards as general secretary of the South African Council of Churches.

Already a high-profile figure before the 1976 rebellion in black townships, it was in the months before the Soweto violence that he first became known to white South Africans as a campaigner for reform.

Saving suspected police informer

His efforts saw him awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 in what was seen as a major snub by the international community to South Africa’s white rulers.

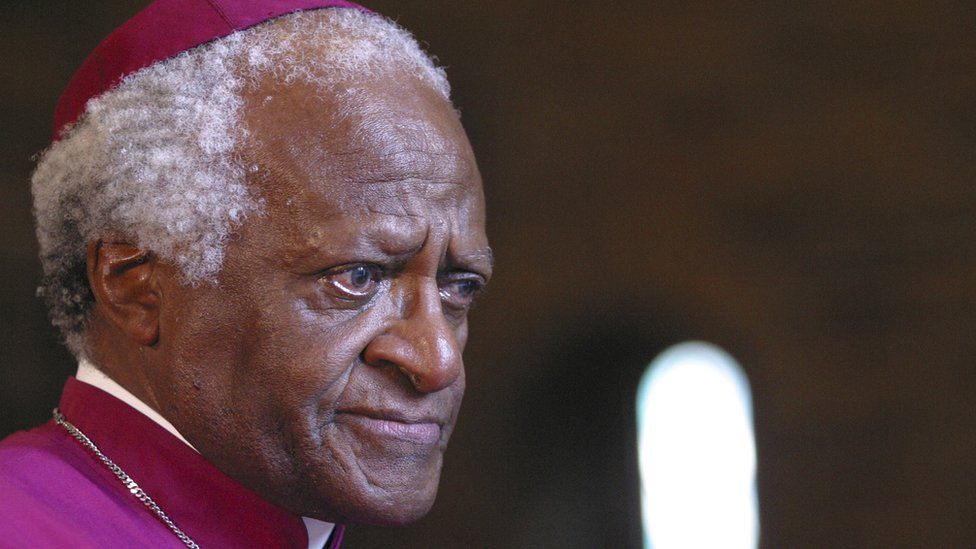

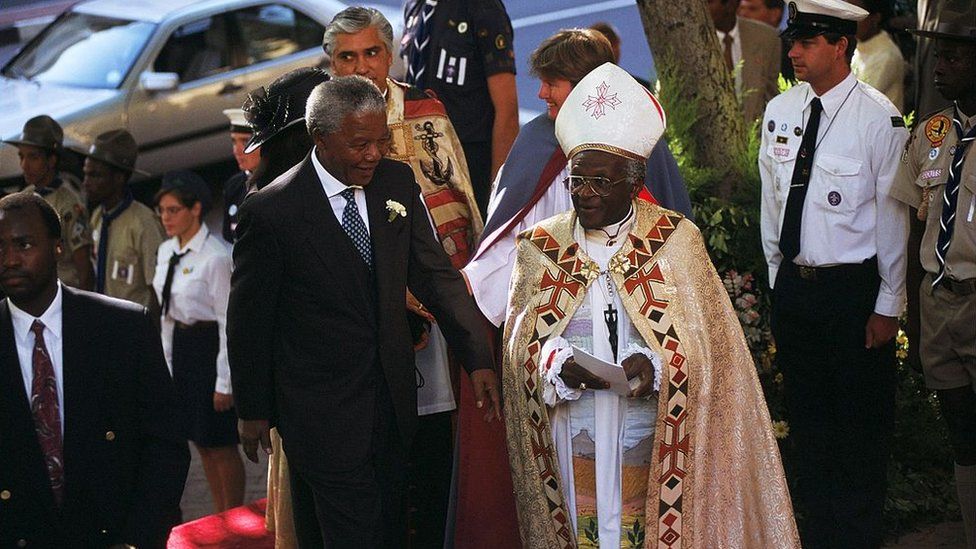

Desmond Tutu’s enthronement as Archbishop of Cape Town was attended by the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Robert Runcie, and the widow of Martin Luther King.

As head of the Anglican Church in South Africa, he continued to campaign actively against apartheid. In March 1988, he declared: “We refuse to be treated as the doormat for the government to wipe its jackboots on.”

Six months later, he risked jail by calling for a boycott of municipal elections.

He was caught in a cloud of tear gas in August 1989, when police took action against people leaving a church in a township near Cape Town, and the following month he was arrested after refusing to leave a banned rally.

As archbishop, his calls for punitive sanctions against South Africa struck a chord throughout the world, especially as they were coupled with a total condemnation of violence.

In 1985, Tutu and another bishop bravely and dramatically rescued a suspected police informer as he was being assaulted and about to be burnt to death by an angry mob in a township east of South Africa’s main city, Johannesburg.

The clergymen pushed through the mob and pulled to safety the bleeding, half-conscious man, just before the petrol-doused tyre around his neck was set alight.

Tutu later returned to rebuke the man’s attackers, reminding them of “the need to use righteous and just means for a righteous and just struggle”.

Tutu warmly welcomed the liberalising reforms announced by President FW de Klerk soon after he took office. These included the lifting of the ban on the African National Congress (ANC) and the release of Nelson Mandela in February 1990.

Soon afterwards, Tutu announced a ban on clergy joining political parties, which was condemned by other churches.

On Israel and the Palestinians

He was never afraid to voice his opinions. In April 1989, when he went to Birmingham in the UK, he criticised what he termed “two-nation” Britain, and said there were too many black people in the country’s prisons.

Later he angered the Israelis when, during a Christmas pilgrimage to the Holy Land, he compared black South Africans with the Arabs in the occupied West Bank and Gaza.

He said he could not understand how people who had suffered as the Jews had, could inflict such suffering on the Palestinians.

Desmond Tutu was a great admirer of Nelson Mandela, but did not always agree with him on issues such as the use of violence in pursuit of a just end.

In November 1995, Mandela, by then South Africa’s president, asked Tutu to head a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, with the task of gathering evidence of apartheid-era crimes and recommending whether people confessing their involvement should receive amnesty.

At the end of the commission’s inquiry, Tutu attacked South Africa’s former white leaders, saying most of them had lied in their testimony. The commission also accused the ANC of committing human rights abuses during its fight against apartheid. Both sides rejected the report.

Reduced to tears

Tutu was often overcome by the pain of those who had suffered under apartheid and, on more than one occasion, was reduced to tears.

He also found much to criticise in South Africa’s new black-majority government. He launched a stinging attack on the ANC administration led by President Thabo Mbeki.

He said the ANC had not done enough to alleviate poverty among the poorest in the country and that too much wealth and power was concentrated in the hands of a new black political elite.

He later urged Jacob Zuma, who had been accused of sexual crimes and corruption, to abandon his attempts to become president.

He was also vocal in his condemnation of Robert Mugabe, once describing the Zimbabwean president as “a cartoon figure of an archetypical African dictator”. Mugabe, in turn, described Tutu as “evil”.

He could also be critical of his own Anglican church particularly in the aftermath of the row over the ordination of gay bishops.

Ever the rebel

“God is weeping,” he once said when he accused the church of allowing an “obsession” with homosexuality to take precedence over the fight against world poverty.

He returned to the subject of poverty when he visited Ireland in 2010. He urged Western nations to consider the effect of cuts in overseas aid in the wake of the economic downturn.

Tutu formally retired from public life in the same year to, he said, spend more time “drinking red bush tea and watching cricket” than “in airports and hotels”.

But ever the rebel, he came out in support of assisted suicide in 2014, stating that life should not be preserved “at any cost”.

Contrary to the views of many church figures, he held that human beings had the right to choose to die.

He said his great friend and fellow campaigner Mandela, who died in December 2013, had suffered a long and painful illness which was in his opinion “an affront to Madiba’s dignity”.

In 2017, Tutu sharply criticised Myanmar’s leader and fellow Nobel Peace laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi, saying it was “incongruous for a symbol of righteousness” to lead a country where the Muslim minority was facing “ethnic cleansing”.

Later that year, he opposed Donald Trump’s decision to recognise Jerusalem as the official capital of Israel. “God is weeping,” he wrote on Twitter, over this “inflammatory & discriminatory” act.

A small man, “the Arch”, as he was known, was gregarious and ebullient, emanating a spirit of joy despite his intense sense of mission.

He was witty, and his conversation was frequently punctuated by high-pitched chuckles.

But beyond this, Desmond Tutu was a man of impeccably strong moral convictions who strove to bring about a peaceful South Africa.

Source: BBC News

***************************************************************

Desmond Tutu – the staunch and steadfast healer of a nation

By Andrew Harding

Desmond Tutu is remembered with so much joy and affection by so many different people around the world today, that it may seem hard to imagine a time or place when he was viewed, not as a courageous moral crusader, but as a devil.

It was the mid-1970s, and South Africa was ruled by a white-minority regime through a brutal system of racial apartheid. Nelson Mandela was in prison and his Soviet-backed liberation movement, the ANC, was outlawed.

Increasingly, white South Africans focused their fears and hatred on a diminutive but outspoken Anglican priest, recently appointed to a prominent Church position in Johannesburg.

“Tutu was the devil incarnate. Literally. One of our family friends said that. He was the embodiment of evil, and the hatred was just extraordinary,” remembered John Allen, a white journalist who later became Desmond Tutu’s official biographer.

“It was an era when the leadership of the liberation movements was banned, jailed or in exile, and here was this person who was saying what most black South Africans felt. Tutu really was public enemy number one, when Mandela was out of sight, out of mind. He had this extraordinary power to communicate. He would not honey his words so as not to offend white Anglicans,” said Allen.ADVERTISEMENT

From his pulpit, Tutu spoke out against apartheid in a city where black people – their lives controlled by strict racist laws – required special passes simply to walk into “white” neighbourhoods.

“Tutu wasn’t a front for political movements. I think that’s what gave him his moral and spiritual freedom,” said Peter Storey, who led South Africa’s powerful Council of Churches. “It made him very powerful because he was up against an apartheid government that wrapped itself in the Church… and yet here was this black Anglican, able to hit the regime at one of their most vulnerable points.

“Desmond could point out to them – if you claim to be Christian, how can you possibly treat my people like this? This is why he was such an irritant to them.”

Frank Chikane, a prominent liberation leader who was poisoned, and nearly killed, by the same apartheid security forces that also looked for ways to silence Tutu, said: “Tutu was the face of the liberation struggle. The voice of the people. He was a key prophetic voice. But he was non-violent, from beginning to end.”

“It was a very scary moment,” Peter Storey recalled, of the time when he and Tutu were kidnapped and taken into the bush by armed men who said they had instructions “to kill us”.

“For some reason they let us go. Later… we were driving down the road back to Pretoria when Desmond said, ‘let us pray.’ He was at the wheel… and his eyes were closed. So, I held the wheel. I didn’t want to give death another shot at us so soon afterwards.

“But that was Desmond. Nobody understands him unless they understand how deeply he was a man of prayer. I remember him saying, ‘I’m not afraid of these people, because the worst they can do is kill me. And I’m not afraid of death,” said Peter Storey.

But Tutu – increasingly prominent as the face and voice of the liberation movement – combined fearlessness with a famously mischievous sense of humour, which often helped him to diffuse tensions when confronted with angry crowds in black townships, often after funerals.

“He had the ability to channel people’s anger, and then the ability to say ‘we are better than those people who are up against us, we don’t have to be like them,” Peter Storey said.

“And he would use humour at times like that. At the very darkest moments you would hear this diminutive bishop stand up and say to the regime, ‘why don’t you join the winning side before it’s too late?’ And people would laugh. But they would also know he was telling the truth because he was so utterly convinced that justice would prevail.”

John Allen recalled: “There is a giggle. But to me it’s a cackle. Mostly it was uproarious laughter. And he used to say that laughing is very close to crying.”

Abroad, Tutu was also known for his humour when engaging with foreign leaders and pushing for the imposition of sanctions against South Africa’s apartheid government, but he could be brutally frank too.

“He was very critical in terms of campaigning for sanctions. He was key, there’s no doubt about it. He came at the right time,” recalled Frank Chikane.

“Tutu was scathing of the blindness of people who – for economic and political reasons – had a stake in preserving white dominance in South Africa. His opinion of Ronald Reagan was scathing. He called him [a racist]. Tutu’s role was to be clear cut, and not to allow himself to be sucked into the ifs and buts and compromises,” said Storey.

Later, in the aftermath of South Africa’s first democratic elections and the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to delve into the crimes of the apartheid era, those working closely with Tutu saw his public tears, and frequent songs, as the work of a man trying to hold a mirror up to a deeply damaged society.

“There were many moments when he would cry,” said Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, who served on the TRC’s human rights violations committee.

“And he started the practise of singing… about the pain of our past. It was almost as if he was carrying the whole country on his shoulders. He walked into the room and you could feel the sense of hope – no question about it. He was almost like royalty, representing the journey towards freedom for everybody. He was driving the country towards peace and that process (at the TRC) would never have been what it was without him.”

Peter Storey said: “We needed a healer. Tutu became the nation’s pastor and helped us navigate that road to healing. The Truth commission became a safe space for people to share their pain. And also for the bad guys – if they were willing – to come and find some kind of healing themselves. And Desmond was, I think, the perfect person to help that happen while maintaining that incredibly steely strength which refused to be pressured… particularly by the ANC.”

In more recent years, Tutu became fiercely critical of the ANC’s failures in government, in particular its slide towards corruption. But President Jacob Zuma’s administration chose to ignore, or sideline the archbishop, even attempting to prevent him from attending Nelson Mandela’s funeral.

So how, in old age, did Tutu judge South Africa’s current struggles – the inequality, unemployment and violence that continue to plague so many communities?

“I remember sitting with him not all that long ago and him saying, ‘You know, Peter, we understand human nature. And so we shouldn’t be surprised. But we are allowed to be very, very sad,'” said Peter Storey.https://emp.bbc.com/emp/SMPj/2.44.10/iframe.htmlMedia caption,”The Sun has gone down”: Watch South Africans’ reactions to the death of Archbishop Desmond

Source: BBC News