Scene but not heard: The silent struggle of Black women in media

By Carolyne Bergeron

At two years old, Amatur Rahman Salam-Alada suffered a brain injury that would change her life forever. Initially diagnosed with hydrocephalus and later a benign tumor, Salam-Alada would spend a year of her life fully blind. After regaining 75 per cent of her vision, she developed a deep appreciation for storytelling, but it wasn’t until years later that she would pursue a career in filmmaking.

Salam-Alada first discovered her love for film at 13 years old when she had to make a skit for a school assignment.

“I like that you could just visualize the story as it was happening,” Salam-Alada said. “Then when I was about 19 or 20, the interest in film and TV kind of kicked in and I found a way to get into it professionally.”

Amatur Rahman Salam-Alada (right) filming with Beatrice Viladelagado (middle) and Nicky Shaw (left) on Feb. 3. 2024. Photo courtesy of Amatur Rahman Salam-Alada

She went on to study journalism at Carleton University and entered her first film, Shaded In in May 2023 at Kino Ottawa, the short film festival and was later premiered at the Mayfair theatre in April 2024. But as a Black, Muslim, visually impaired woman, she quickly realized the industry was not built for people like her.

Black women have long faced systemic barriers in media, from being overlooked for leading roles in film to being underrepresented in journalism and broadcasting. The consequences of this go beyond career opportunities, but deeply affect the mental health, self-worth and sense of belonging in Black women in the public eye.

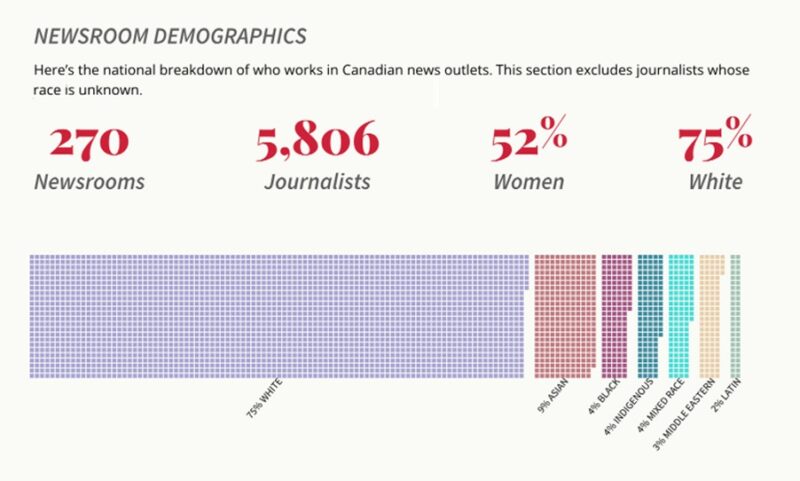

According to a 2024 Canadian Association of Journalists survey, 75 per cent of journalists in Canada are white, the remaining 25 per cent being of Asian, Black, Indigenous, Middle Eastern, Latin and mixed-race descent.

“There’s been so many incredible journalists that I know, Black journalists, racialized journalists, that have worked really hard, but they can’t stay where they are because they’re not being given employment or opportunities for solid employment that is consistent,” said Garvia Bailey, a journalist, broadcaster and co-founder of the podcast production company Media Girlfriends.

Edited infographic provided by Canadian Association of Journalists stating the percentage of race in newsrooms across Canada. (Canadian Association of Journalists)

The survey results suggested that white journalists held more senior and stable jobs, with a majority of white men being in leadership in newsrooms. However, newsrooms across Canada have begun to make efforts to include diverse voices.

Bailey’s first job was with the CBC after she pitched her experience being a Black woman in Canada for CBC Radio’s Outfront. She was offered the position of associate producer and worked there for 12 years.

“From the beginning, I liked that the CBC took a chance on me, and I know for a fact that they probably took a chance on me because they didn’t have voices like mine in the mix,” Bailey said.

A 2021 McKinsey & Company report found that Black professionals in film and TV face systemic barriers that impact diversity on television, revealing that less than six per cent of the writers, directors and producers of U.S.-produced films are Black.

Although the prominence of Black leads has improved – for example Halle Bailey as Ariel in the Little Mermaid, or Cynthia Erivo as Elphaba in Wicked – the film industry has long limited Black women to supporting roles and stereotypes, restricting them from leading roles and positions of leadership on set, the report highlighted.

Black women often struggle with a lack of visibility and when they are represented, their portrayals are frequently stereotypical or negative.

“The Doll Test” conducted by doctors Kenneth and Mamie Clark in the 1940s, demonstrated how Black children as young as three years old internalized negative ideas about their racial identity due to media and societal influences. When presented with Black and white dolls, most Black children associated positive traits with the white dolls and negative traits with the Black dolls.

The study highlighted the damaging effects of systemic racism and a lack of positive representation. Despite progress, Black women continue to navigate the mental and emotional toll of being underrepresented or misrepresented in media, shaping their self-perception and sense of belonging in society.

“I think [the Doll Test] really opened my eyes to how important what we’re consuming through the media is, and in this day and age, it’s very obvious what the beauty standard is,” said Faisa Omer, a psychotherapist and counsellor for racialized students at Carleton University. “The beauty standard is not Black, does not have the features that Black people typically have, like our nose or our hair or our skin complexion.”

Faisa Omer, counsellor for racialized students at Carleton University on Feb 20. 2025. (Carolyne Bergeron)

For the media to contribute meaningful representation, Omer said she believes that more Black people need to be seen in TV shows as main leads, as romantic interests and for non-Black audiences to hear more Black stories being told.

Cheryl Thompson, Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Black Expressive Culture and Creativity and an associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University, said the only way things will change is with real investment at all levels of society—top, middle, and bottom.

She highlighted the ongoing issue of colourism in media representation, emphasizing that while progress has been made, there is still a lack of diversity in the representation of Black women across different skin tones.

“It used to be like that back in the ‘90s, light and bright would always get the shine, and then you would see the dark-skinned women being treated differently or getting different kinds of roles,” Thompson said.

Although representation of dark-skinned women has increased in recent years, with actresses like Viola Davis leading multifaceted roles, Thompson noted that women with medium skin tones are still largely absent from mainstream media. She attributes this to both aesthetic choices and a long-standing Eurocentric gaze in the industry.

“A lot of producers and directors don’t actually know how to frame people in the middle range of skin tones,” Thompson said. “If you’re very dark, they know how to play with shadows. If you’re very light, you’re basically white, and they know what to do with that. But if you’re somewhere in the middle, it’s like they don’t know how to work with it.”

This erasure not only limits representation but also reinforces a narrow beauty standard that excludes a significant portion of Black women. Thompson argues that this is deeply ingrained in racial hierarchies dating back to colonial classification systems.

The idea that only the extremes of Blackness, either very dark or very light, are “aesthetic” enough for media contributes to feelings of invisibility and exclusion.

For Salam-Alada, these barriers in media representation are not just statistics or studies, but rather they are lived experiences.

Instead of being discouraged, Salam-Alada is using her unique perspective to create films that reflect the world as she sees it: a world where Black women take up space as leads, storytellers, and decision-makers behind the camera.

“The idea is to be loud, to be yourself, and to show your gifts. The world is not going to like that, because it is just the way [it’s] built right now,” Omer said. “Remember that you are your ancestors’ wildest dreams.”

For Salam-Alada, that dream is already in motion.

From balancing academics to proudly representing her Caribbean roots, Carolyne Bergeron is a force of resilience and passion. Born and raised in Jamaica, she found her sense of purpose in the cool parish of Manchester, where she spent much of her formative years. Deeply influenced by her cultural heritage and family values, Carolyne carries a strong commitment to community and identity. She is currently a second-year student at Carleton University, pursuing a double major in Journalism and Communication and Media Studies. Her experiences continue to shape her vision for the future. Carolyne hopes to build a career in media production and public relations, using storytelling to amplify Caribbean voices and inspire meaningful change.”