Copenhagen: A review

by Noha Abdelmoaty

Copenhagen, agonizing and painful, hurts less after we separate from it, when we put it in conversation with other works of art and when we see it in the light of our experiences. The characters in the play are all dead and in their death, they want to know why physicist Werner Heisenberg, visited Copenhagen in 1941. Only in their death, when the souls of Heisenberg and his hosts, physicist Neils Bohr and Margrethe Bohr replay the events of the night of Heisenberg’s visit, are they able to understand why he went to Copenhagen. Heisenberg himself discovering that the truth was buried so deep inside him that he could never see it in his life. For years, he was questioned about this visit and the more he explained, the deeper the uncertainty became.

At the centre of the stage is time, non-existent and infinite. The characters realize they can dive into their past, ask questions they never did in their life since now, no one can get hurt. They replay the same night repeatedly to rediscover their feelings and their motifs and how they influenced their actions during a time of war. Heisenberg and Bohr blame each other and themselves for their research being essential to the creation of the atomic bomb. Was Heisenberg betraying his country by not engaging in this research, what other options did he have?

The play is an imagination that materializes the humanness of mathematics. In life, like in Maths, there are concepts our minds cannot grasp about the world within and around us. Nevertheless, we have no other choice but to accept and build upon them. Resembling an inconclusive mathematical proof, the play is tired, hopeless, and regretful, capturing the pain and violence that the characters imposed and experienced.

A week after I saw Copenhagen, as I was preparing to write this review, I heard Gilberto Gil’s live performance of the song Iansã play in my head. Translated from Portuguese, his introduction to the song goes:

“This music that I sing now was made with Caetano, Bethania recorded it. It is called Iansã and I like it a lot because many of us intuitively sense the existence of immanence and transcendence…One day I’m going to redeem myself entirely from the sin of intellectualism, God willing. I won’t have any more need to say anything, to think in terms of everything, to try to explain to people that I’m not perfect but the world isn’t either; and that I don’t want to be the owner of the truth, that I don’t want to singlehandedly do work that is meant for all of us and for someone else: time, the true great alchemist, the one who really transforms everything. A tiny grain of sand is what I am. But the grain of sand has already managed to be as big or bigger than me being very small and not needing to show more, to stay there in silence”[1].

To enjoy this play, we have to activate our senses, allow ourselves to forget the arguments, the details, the justifications, the lectures, observe the fog rising from the stage, and react to the melodious and trained voice of Margarethe. Margarethe: a woman who listens more than she speaks, knows her way to the truth and despite the noise remains connected to it.

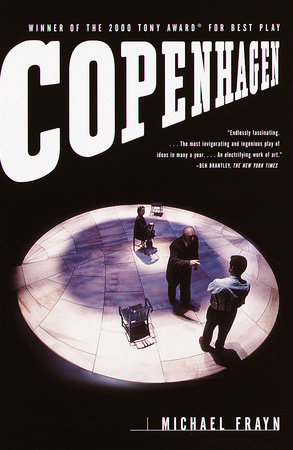

Copenhagen is a play written by Michael Frayn. This review is of its production at the National Arts Gallery in Ottawa, directed by Jillian Keiley.

[1] Recording of Gilberto Gil’s live performance of Iansã: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q03QjHyDyMw

Noha Abdelmoaty is from Alexandria, Egypt. she currently lives in Ottawa and works as a Settlement Counsellor. She studied Women’s Studies, Mathematics and Gender Studies. She loves learning new languages because they open windows to different places. Noha has lived in Egypt, the USA, Spain and Canada. Alexandria is always in her heart and she is determined to love where she lives and live where she loves.